Hilti Art Foundation

«arteria» came to Bülach. The result is a feature article about my work and my career.

It was a special studio visit: Paul Herberstein and Petra Rainer spent half a day in my studio. The editor-in-chief asked the questions, the photographer discovered the details, and I worked at times, and at times answered those questions.

Carving a Career out of Wood

If Marcel Bernet reaches for a power saw in his studio, the muses begin to sing. The Swiss artist creates fine art out of raw materials. We were granted an exclusive glimpse over his shoulder.

If Marcel Bernet reaches for a power saw in his studio, the muses begin to sing. The Swiss artist creates fine art out of raw materials. We were granted an exclusive glimpse over his shoulder.

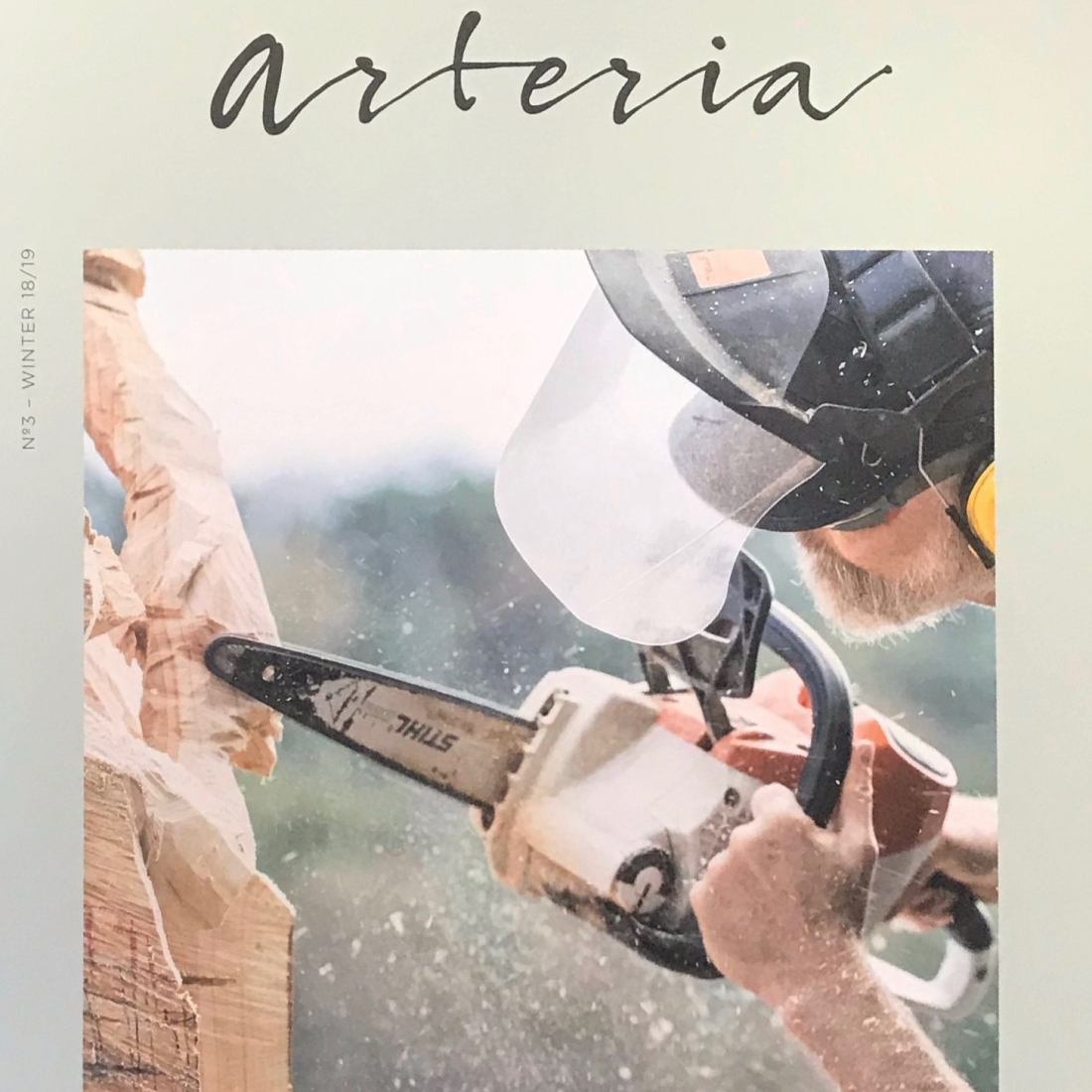

In the middle of a forest a chainsaw starts up – a familiar sight and an even more familiar noise. Rattling noisily, it digs into the rough bark of a tree trunk, fine chips fall to the ground. But it is not a lumberjack who goes about his daily business here – but rather an artist. Kitted out with a helmet, ear protectors and steel cap shoes, Bernet stands in front of his studio and works carefully on a sculpture. His workshop is tucked away in a factory in Bülach (which was shut down many years ago) and is surrounded by a magnificent natural landscape. Here, there is a kind of shield against the roar of everyday life, yet at the same time a never-ending source of the material from which his art is born: wood.

Bernet gently models a female figure from a tree trunk with a handheld cordless saw. Again and again, the tall, slender man pauses to examine his own arm. He examines the hands and fingers carefully and checks that all the joints are connected anatomically. The block of wood opposite him begins to take shape and vitality with each of his cuts. One gets the feeling that the artist and the sculpture have long been absorbed in a silent dialogue with one another – a conversation that ends only when a finished piece of art is formed out of the wood – in body and soul.

Now the chainsaw is silent in the Bülach studio – art is taking a break. For up to three months at a time, Bernet works on a sculpture. Sometimes – in order to be able to approach his work again with fresh eyes – Bernet allows himself long breaks before continuing to work.

Now the chainsaw is silent in the Bülach studio – art is taking a break. For up to three months at a time, Bernet works on a sculpture. Sometimes – in order to be able to approach his work again with fresh eyes – Bernet allows himself long breaks before continuing to work.

“I am often amazed at how I finally reach a certain result. The symbolism and statement of a work of art is frequently only revealed at the very end. Sometimes they not even reveal themselves until they are completed or shown in an exhibition,” says the 60-year-old Swiss, whose artistic career – in addition to a successful career as a PR consultant and coach – only picked up speed about ten years ago. “Ever since I can remember, I’ve wanted to make art. As a teenager, I was passionate about visiting museums and galleries, and I have regularly attended art classes over the years.”

The “Aha!” moment finally came during a visit to a gallery in Zurich. Marcel Bernet recalls: “Stephan Balkenhol’s impressive sculptures immediately left me spellbound.” All of a sudden, Bernet understood the tools he needed to become an artist: a chainsaw and some wood. “At the age of 50, I had the opportunity and the maturity to give time and space to art alongside my day job. The two were not opposed to each other. I can now say with much confidence that I am – and I can do – both,” explains Bernet, radiating profound serenity. But unlike Balkenhol, Bernet creates art exclusively with a chainsaw and refrains from adding finer detail with a carving knife. “That’s just how it feels to me. As if I were painting with a thick felt-tip pen.”

As proof, the wood sculptor brings out a few sketchbooks from a drawer. “I prefer sketching my ideas with chalk pencils. This gives me a first impression of how the finished sculpture might look later.” The key word here is ‘ideas’: where does an artist like Bernet get his from? He smiles quietly. “I’ve never really experienced any sort of creative crisis or emptiness. I find there is a basic song of ideas in me: when some of the voices fall silent, others remain and I listen to them, thinking of new ways a work of art could emerge. Images of everyday life appear as flashes of inspiration: encounters with people, exciting situations or just photos from magazines or the internet.”

As proof, the wood sculptor brings out a few sketchbooks from a drawer. “I prefer sketching my ideas with chalk pencils. This gives me a first impression of how the finished sculpture might look later.” The key word here is ‘ideas’: where does an artist like Bernet get his from? He smiles quietly. “I’ve never really experienced any sort of creative crisis or emptiness. I find there is a basic song of ideas in me: when some of the voices fall silent, others remain and I listen to them, thinking of new ways a work of art could emerge. Images of everyday life appear as flashes of inspiration: encounters with people, exciting situations or just photos from magazines or the internet.”

The subtle, creative process is juxtaposed with the raw materials and the physical work – or, as the artist himself jokingly calls it, “sweat and sawdust”. Today is no different. The wood sculptor pulls a massive, raw tree trunk out into the open with a forklift. A bold pink “B” is emblazoned on the bark of the rare cedar. “B” for Bernet, marked by the local forester when he fells certain trees in the neighbouring forest and then offers them to the artist for sale.

Marcel Bernet reaches for heavy equipment: a gasoline chainsaw with 90 cm saw blade. Loud and shrill, it cuts off the upper part of the trunk. “You can only get a clean cut for the desired size with a professional tool like this,” the experienced sculptor explains. Then, with red chalk, he marks the outline of the planned work on a freshly cut surface. From its raw state, Bernet gradually starts to shape the wood into the figure it will later become. “I always start from the top and need at least the outline of a head or a face so that the artwork can begin to speak to me,” the artist adds, providing insights into his personal creative process. “After that I sometimes feel like I’m a servant to the material. A kind of dance starts between what I want and what the object wants from me.”

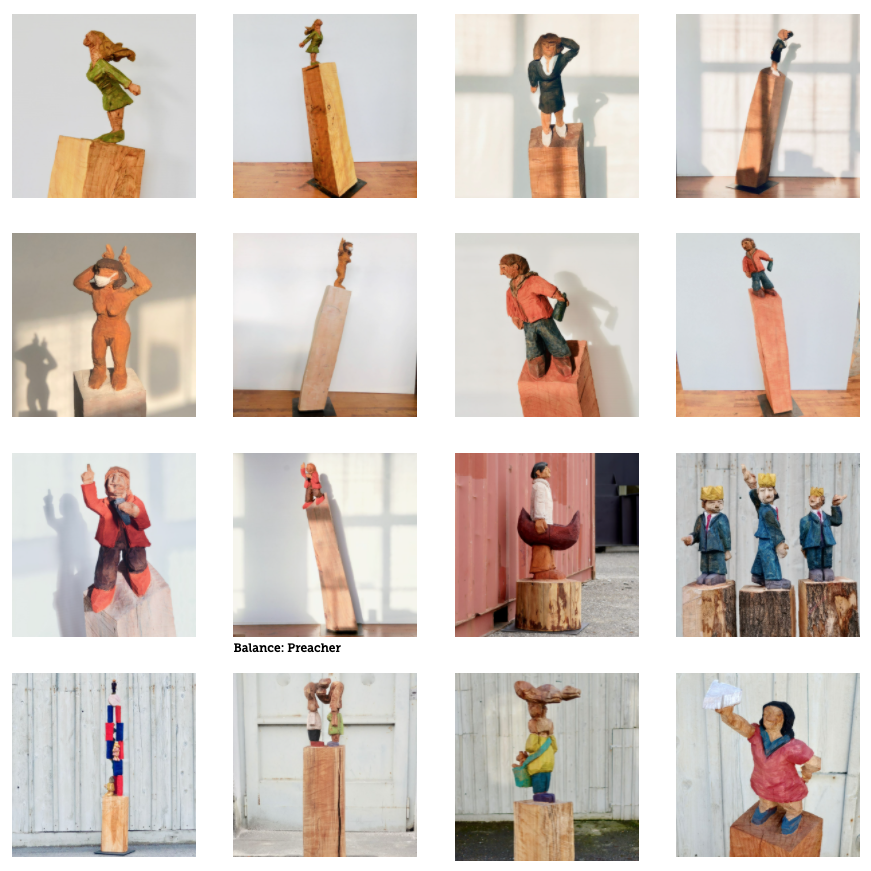

When the artist and artwork are all danced out, they take a break from one another. The finished sculptures often stand for weeks before the artist comes into contact with the wood again: when the raw form is finally painted. “It’s a completely independent process and a pleasant contrast to the physically demanding work with the power saw,” explains Bernet. The colouring provides something almost meditative for him. Normally only natural shades are used for the pigments – such as red Tuscan soil. “I use colour only for simple accents for the eye. The shape has to be just right. When painting, I simply stroke the material.”

When the artist and artwork are all danced out, they take a break from one another. The finished sculptures often stand for weeks before the artist comes into contact with the wood again: when the raw form is finally painted. “It’s a completely independent process and a pleasant contrast to the physically demanding work with the power saw,” explains Bernet. The colouring provides something almost meditative for him. Normally only natural shades are used for the pigments – such as red Tuscan soil. “I use colour only for simple accents for the eye. The shape has to be just right. When painting, I simply stroke the material.”

Exhibitions and vernissages ultimately provide their own artistic strokes. Bernet openly admits: “Recognition and applause are important to me. Not least because one can only experience one’s own art in exhibitions and through the eyes of others.”

The visit to the studio is coming to an end. Bernet leads the way to several already finished sculptures in the outer area of the studio and shows us his “pantry” comprised of logs, most of them delivered directly from the surrounding forest. “I like their smell and structure. In a similar way to human wrinkles, the growth rings of differing thicknesses indicate a tree’s varied life,” enthuses the artist. “Even the most unsightly parts of it: knots or cracks. Wood grows and changes in a similar way to us. And I can give a second life to the wood through my work.”

As a farewell, Bernet becomes thoughtful for a moment. “I hope I was not too long-winded and open with my remarks?” Not at all. Ultimately, it is only possible to look so far into the soul of an artist, and in the wood that shapes his career.